My lovely friend Mary MacDonald dropped the seed for this idea, in my mind. She is a poet. Also a child psychologist. A dog-mama. A walker and a writer and an integral part of the Whistler Writing Society and Festival. A short story author. (See her collection The Crooked Thing at https://marymacdonald.ca.) A bird-watcher. Read her beautiful homage to bird-watching in the Pique, where she wrote this:

Soon it will be winter. There will be swirling patterns of birds murmuring. A great blue heron I have seen before will hunch again over on the edge of icy Green Lake while it’s snowing, its neck tucked in against its chest. There will be bald eagles and osprey. Swallows, woodpeckers, chickadees, kinglets, northern flickers. Steller’s jays shook, shook, shooking at my window, looking for seeds as their food source grows scarce. Song sparrows and pine siskins. Warblers and vireos. Buffleheads, cormorants, and mergansers. Ducks pitching their sounds across the lake like oboes. The thrill of trumpeter swans arriving on their migration path to Alaska.

I am insignificant compared to the bird world. Attention-giving has changed me. We carry each other now, birds and me. It’s nature’s way.

How am I going to do this hard thing facing me? As the writer Anne Lamott said of any tough task—you take it bird by bird.

Mary MacDonald

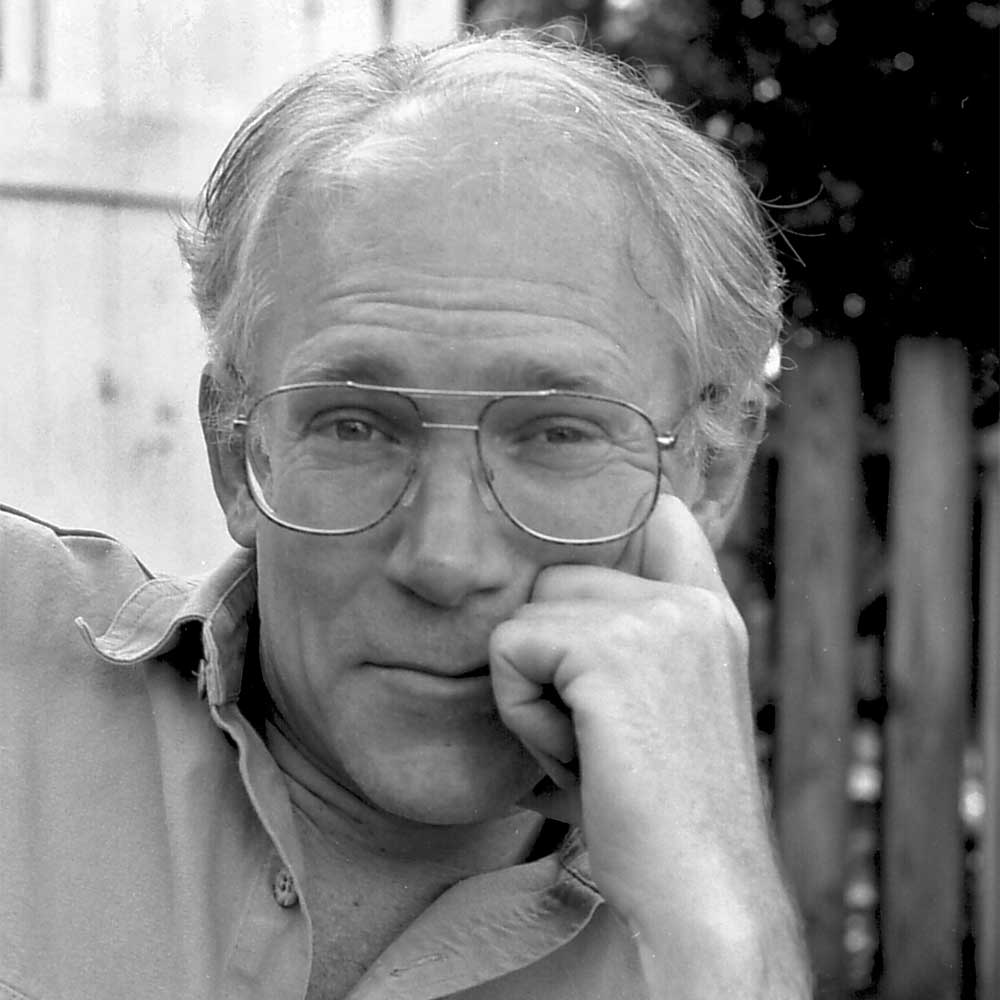

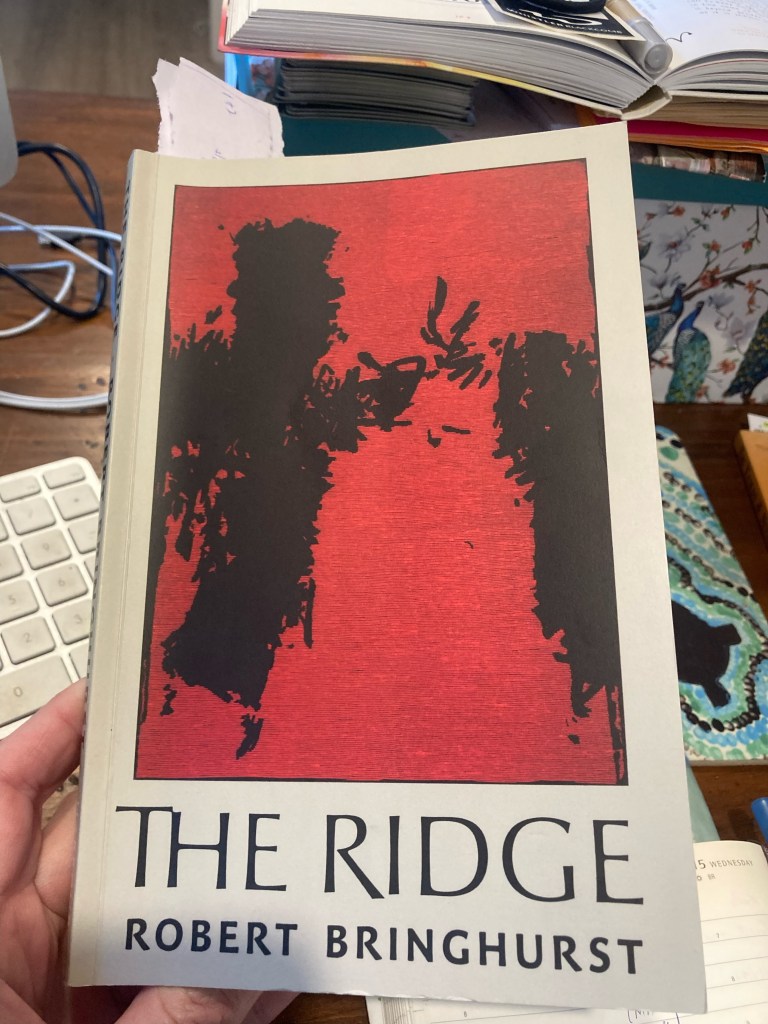

This fall, at the Whistler Writers Festival, Mary had organized to bring the brilliant poet and linguist, Robert Bringhurst, to Whistler, to read from his recent collection, The Ridge. Bringhurst might be one of Canada’s foremost “men of letters”, the author of 23 poetry collections, 17 books, and 5 books of translation, having immersed himself in Haida, Navajo, Greek and Arabic during his life long love affair with language. He’d not been to Whistler for decades, and set out early the day of his reading to hike up Singing Pass. Unlike almost everything else here, the trail is much the same. Same wash-outs, same creek crossings, same ancient rumblings. At close to the last minute, I stepped in for Mary to interview Robert – her oncologist had given her a strict “avoid gatherings” vibe, and Mary called in the understudy, which had been a back-up plan for months but not one we thought we’d have to deploy. It was a personal and professional highlight, to be in conversation with such a thoughtful and passionate human, and also hard to celebrate as a win, because I sensed what it cost my friend to have to step aside. In our conversations leading up to Robert’s visit, as part of the torch-hand-off, Mary said a few times, in relation to her interpretation of The Ridge, that she finds increasingly that poetry is the thing that can get us through hard moments.

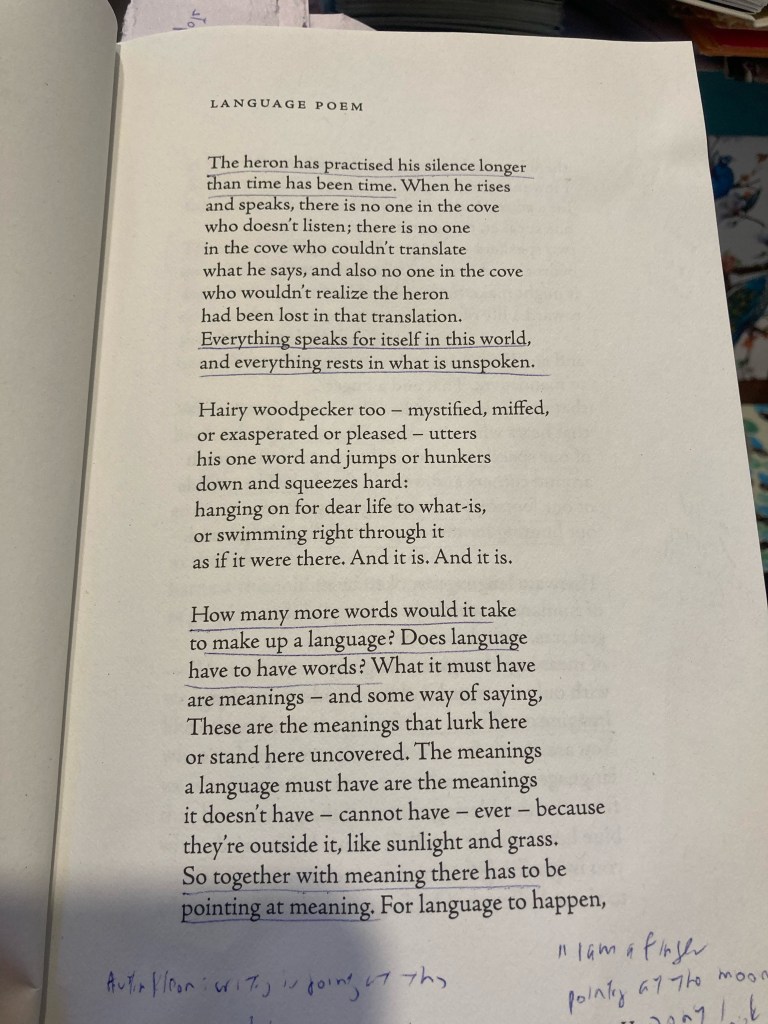

I don’t always read poetry. My attention span and nervous system are rarely in a settled enough state for me to be with 100 dense words. But as I read and underlined and meditated on Bringhurst’s poetry, in the lead-up to the Whistler Writers Festival this year, I could literally feel something happening to me, a kind of dreaminess overtake me, a kind of altered state come upon me, so even as I was loading up the laundry, I was mulling over the rhythm and riddle of Robert Bringhurst’s words, of his questions, “The heron has practiced his silence for longer than time has been time…. Everything speaks for itself in this world, and everything rests in what is unspoken. … How many more words would it take to make up a language? Does language have to have words?… Meaning was here well before you were and will be long after…” (Also, to be true, I had moments of frustration and of forehead-pounding, feeling too dense to get it, or eluded by some deep thought that I’d almost grasped until it slipped away.)

I feel like this book is a real spiritual coming-home, from a really erudite guy with a huge brain. And I think it’s about how do I do something that makes a difference? How does poetry make a difference? He can write anything. Why poetry, to try to shift things forward? What I believe is people turn to poetry in hard times. And why do we? We’re looking for some people to guide us, to root us. It’s kind of an abyss. We don’t know what to do. We know the earth is warming, the ice is melting, the fires are burning, and we don’t really know what to do. I think most people feel hopeless and it isn’t a great place to be. This is a way in. For some reason, we turn to poets in hard times.

Mary MacDonald

Mary’s words made me think that poetry as a special kind of medicine in this world. And I ought to take a small dose of it more frequently. And it made me think of something I heard recently, that art is actually psychoactive – that is, a thing that “produces changes in perception, mood and cognitive processes. Psychedelics (psychoactive substances) affect all the senses, altering a person’s thinking, sense of time and emotions.”

Mary and Kerry Dorey were the two voices who came immediately to mind, when I wondered what it would be like to share poetry with each other. I am so grateful to them for saying yes. (I hope you will too? Just send me a voice memo. I’m literally standing by.)

Here is Mary MacDonald’s poem, If Only.

I’m going to read a poem in the form of a pantoum. If you’re not familiar with the form of the pantoum, it’s actually a very old poetic form that comes from Malaysia. It’s a very structured poem – typically four stanzas. The poet writes 8 lines and the pantoun structure dictates where each line will fall. In my experience, very interestingly and beautifully, actually, the final line ends up being really the gist and the heart of the poem. And I don’t know how that works, but it seems always to be the case. So here’s my pantoum, If Only.

If Only

by Mary MacDonald

I will soon turn to dust

During the next thirty minutes.

It found its footing in October.

Nineteen ballets set to music by Tchaikovsky.

A cello reinvents itself.

During the next thirty minutes.

It is not the whole truth.

Nineteen ballets set to music by Tchaikovsky.

A cello reinvents itself.

I want you to understand it.

It is not the whole truth.

The heron is how I know I’m alive.

I want you to understand it.

Scars criss-cross my body like claw marks.

Three facing forward. One pointing backwards.

The heron is how I know I’m alive.

It found its footing in October.

Scars crisscross my body like claw marks.

Three facing forward. And one pointing backwards.

I will soon turn to dust.